Paysage Vivant, Paysage Vibrant

Experimental is an attribute that has always been closely associated with creation and art.

Experimental cinema is like a probe that scans across lands to find the most hidden and fascinating corners of human perception, testing it without compromise. With Paysage Vivant, Paysage Vibrant, in its Italian premiere, Manifattura Tabacchi has taken a step towards the multidisciplinarity and experimentalism that characterises the modern artistic avant-garde.

The selection of cinematic works was made by Emmanuel Lefrant, video artist and director of Light Cone, a Parisian film archive house. Lefrant chose to show films that were very different from one another but which all have a common thread, which also inspired the title of the festival. Mechanical, urbanised, telluric, isolated, mediated, abstract, the landscape emerges in the widest of varieties, revealed in a wide range of possibilities, each of them unprecedented and original.

Many of Light Cone’s archived videos are currently being shown at Time Machine, an exhibition on moving images curated by Antonio Somaini and taking place in Parma, as part of its inauguration as Italian City of Culture 2020.

The desire to get back lost time, the illusion of stopping in an instant, the paradoxes and the infinite digressions of the imagination on the possibility of escaping the rigid dictatorship of the flow of time, all finding in cinema a possibility of representation that affects the very possibilities of how we imagine time itself: from its acceleration to deceleration, from fixed images to time-lapses, and to the infinite variations offered by editing, the cinematographic techniques of temporal manipulation broaden and remodel the limits of our perceptions, allowing us to see and experience other time dimensions that border on the regions of dream and desire.

Accompanied by the regular and mesmerising sound of the reels turning, the films of Paysage Vibrant, Paysage Vivant are a concentration of stimuli, including archive images, photographs and artisan techniques. Experimental cinema has long been associated with, if not limited to, dimensions of artisan production and the physical material of film. The possibilities offered by working in this way are indeed impressive.

In China Not China (2018, 16mm), Richard Tuohy superimposes around 15 takes of the same scene, in which Hong Kong celebrates the twentieth anniversary of its repatriation to China. The technique of superimposing, apart from deforming the space, induces a sensation of continual impermanence, an unresolved transition that transcends the historic context and embraces universal emotions, redolent of the precarious conditions that are currently unravelling in the territory.

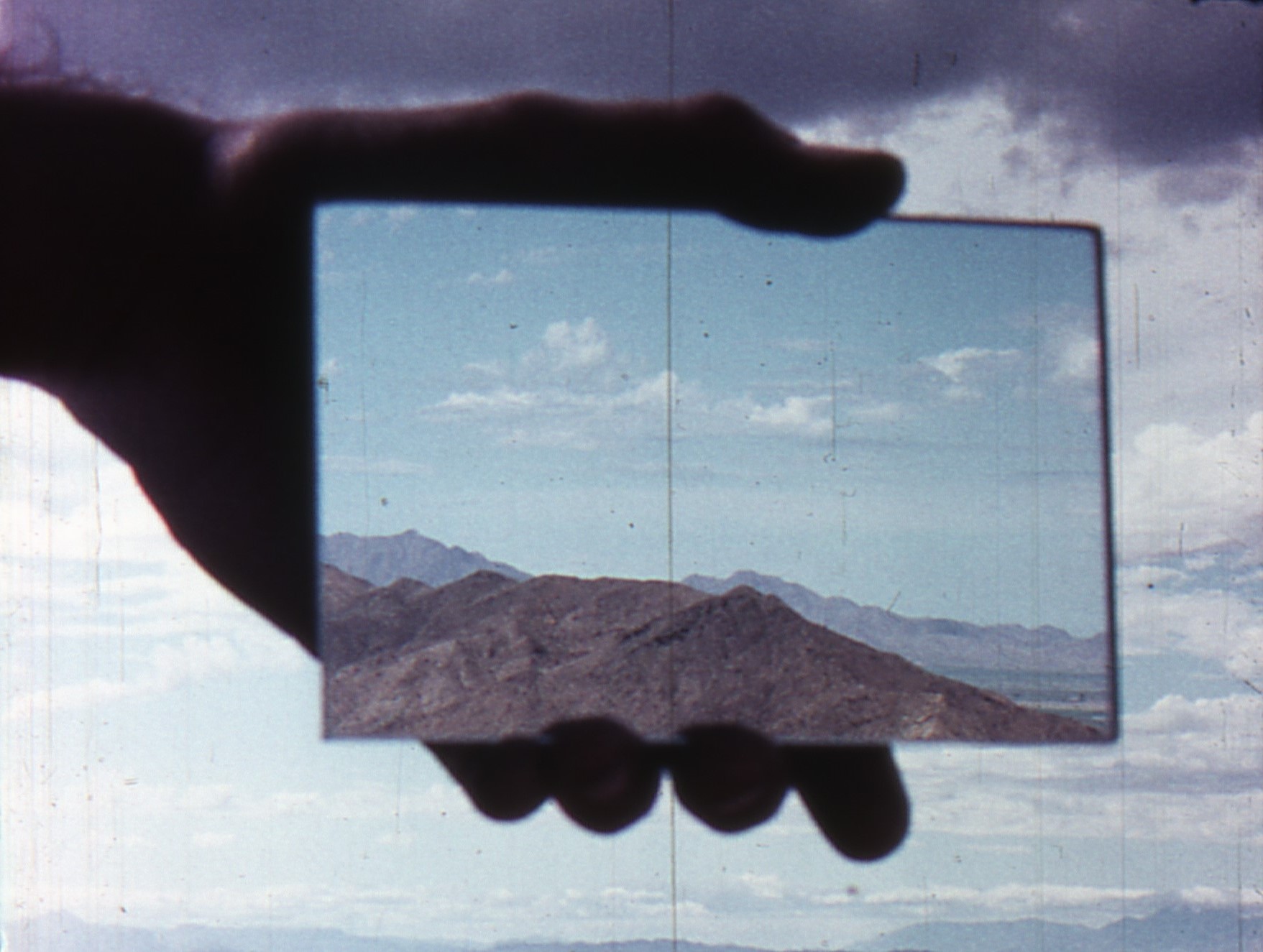

Time-lapse takes precedence in Gary Beydler’s Hand Held Day, a unique sequence of a road in Arizona, that moves from dawn to dusk compressing 14 hours into only 6 minutes. On a small mirror, held in the director’s hand, an entire day flashes by, silhouetted against a pastel coloured sky of fleeting clouds.

Another time-lapse, and one of the most experimental of all of the screenings is Parties visible et invisible d’un ensemble sous tension (2009, 16 mm). Emmanuel Lefrant leaves the earth and its processes of life and consumption the role of acting in this film, which then returns material effects that come close to painting, a painting in movement, which, with the sound of the wild African landscape, becomes a unique living organism.

Set (2016, 16mm) is probably the film which requires the most of its viewers, but it repays them in full. Over 5000 photos of different sunsets run in sequence, following the course of the sun until it sets at sea. The background changes 8 times a second, as all the while the sun maintains its steady trajectory.

Emmanuel Lefrant recalls that, although experimental cinema has a particular relationship with analogue film, it goes beyond this because it exists beyond the means that are employed to create it. The last films in the festival were shot digitally, yet the effect of warmth and nostalgia is preserved to perfection. The landscape is viewed from far off (I don’t think I can see and island, Christopher Becks and Emmanuel Lefrant, 2016), then scrutinised in its most dangerous and devastating drifts (Asleep, Paul Abreu, 2012), then projected into a future of profound desolation and destruction (Le pays devasté, Emmanuel Lefrant, 2015).